Odious Comparison

(c) New York Magazine

November 24, 1986

By John Simon

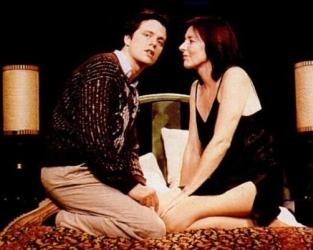

Tiresomely he rehashes the tired argument that life in Communist Russia, un-free, fear-ridden, precarious as it is, is scarcely different from like in the United States, free, easy, and rewarding as it is supposed to be. The problem with this is, first of all, that it is patently untrue; but it is the with-it thing for liberal whippersnappers – who know nothing of life in the U.S.S.R. and not much more about life anywhere – to expatiate on. This kind of simplistic smart-asininity panders to overgrown but underdeveloped collegiate rebels of the sixties – perhaps even to some present-day campus pundits – but cannot provide enough bases for the flimsiest of comedies. In the second place, Reddin's Moscow and New York are equally cliché-studded and sloppily observed. Thus you do not make fun of a typical Russian by representing him as one who never heard of Mayakovsky or Akhmatova; the trouble is that he has heard too much, can recite reams of both poets, and still not learn anything from them – a trouble by not means limited to Soviet Russia. Similarly, the American Secret Service types who detain the hero, expelled from Russia, for humiliating questioning would not camp around like a pair of homosexual comics; surely there would be better things about them ridicule. And for a Columbia graduate student in Russian literature, the hero is far too ignorant of Russian literature, language, and life. Theatre of the absurd must take off from a sense of reality that is then variously exaggerated and distorted; Reddin starts a preposterousness he can neither heighten nor develop. All he can do is repeat and repeat: Highest Standard of Living reiterates its feeble jokes – already dragged out way beyond the point of diminishing returns, assuming there were any returns in the first place – within each act ad infinitum. And the parallel structure – Act I: Moscow, Act II: New York – merely encourages further repetition and schematism. A Russian fan rattles off an endless litany of Little Richard song titles from his record collection. The American hero and a young Russian fanatic vie in reviling Reagan, the American befuddling his opponent by outdoing him – which might be funny if not so dragged out. The hero's confusion when the heroine, a Russian doctor he casually invited to America, actually shows up, as a defector, is interminable, both of them hemming and hawing at unconscionable length. A bunch of vicious, hammer-wielding children are brought on twice in Moscow, their equivalents appearing twice in New York. Dead bodies disappear in a twinkling in both cities; desperate people jump off boats in both. Don Scardino has managed to direct all this sameness with a remarkable about of variety and verve, and John Arnone's sets have a sweetly mischievous naiveté nicely supported by David C. Wollard's costumes and Joshua Dachs' lightning. The acting is consistently good from top to bottom, my special favorites being, aside from Steven Culp's winningly losing hero and Leslie Lyles's touchingly bewildered heroine, Timothy Carthart (who does both Russian and Russianized English splendidly) and Peter Crombie, each in couple of roles, with the rest close behind. But no prodigality of talents in the production can mitigate the crudeness of concept, banality of humor, and sweat under the collar Highest Standard of Living exhibits, reducing it pretty much to the lowest standard of playwriting. Keith Redding is a very good actor, why subtract from this by becoming a very poor playwright? |

DISCLAIMER: This site is a Steven Culp fan site and is not affiliated with Steven Culp, his family or any of his representatives.

Unless otherwise noted, all captures were made by me from videos from various sources. All shows and photos belong to their respective owners.

NO COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT INTENDED!

© 2004-2022 SConTV.com and Steven-Culp.com

Unless otherwise noted, all captures were made by me from videos from various sources. All shows and photos belong to their respective owners.

NO COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT INTENDED!

© 2004-2022 SConTV.com and Steven-Culp.com